Stories of Ellis Island

Albin

Moskelony

From Immigration to Deportation: 1924-1954

After World War I, rising nativism and xenophobia led to calls to curtail immigration–particularly non-Western and non-Northern European immigration. Quotas were set based on the 1890 census in order to minimize immigration from non-Northern European peoples. People in the Western hemisphere were not part of this quota and continued to immigrate into the United States.

At the same time, the National Origins Act of 1924 limited the number of immigrants and the procedures for immigration to the U.S. had also changed. Instead of judging the fitness of would-be immigrants upon their embarkation, people were increasingly required to apply for visas through the U.S. consulate in their country of origin. No longer a place to process immigration, Ellis Island became a place for internment pending deportation. This was a drastic change. Ellis Island was primarily a site to enter the United States as an immigrant. Now, Ellis Island represented a site where you were told you were not welcome and would be sent back where you came from.

The intent of Ellis Island continued to dramatically change. During World War II and its aftermath, Ellis Island housed a number of people deemed undesirable by the U.S. government, including U.S. residents suspected as being Nazis and, after the war, people accused of being communists.

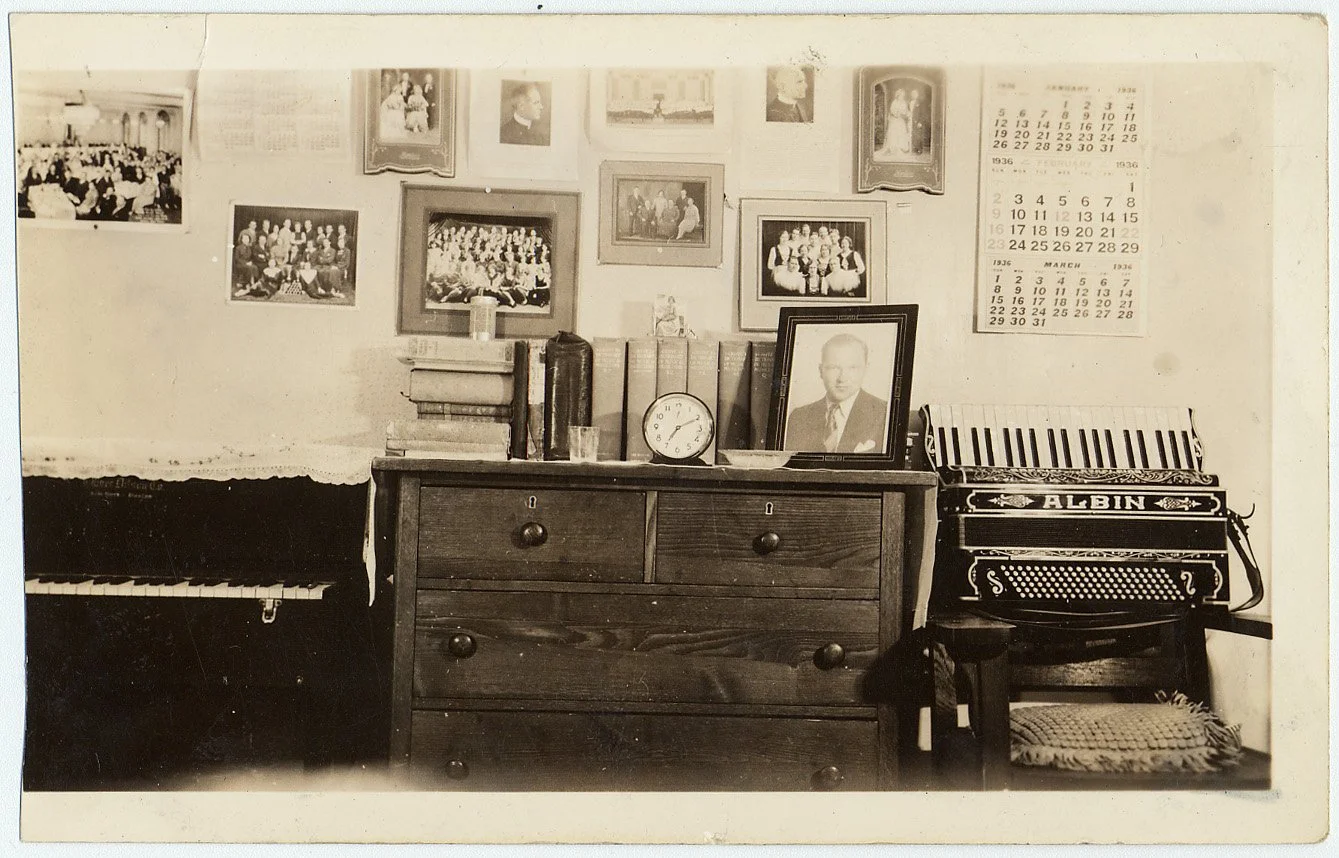

The Story of Albin Moskelony

Albin Moskelony was 23 when he first started working at Ellis Island in 1934. A high school graduate, he was unable to find satisfying employment until he went to the US Employment Service, where he received a lead on a job at Ellis Island in the Public Health Service.

He was hired immediately as a pot washer, then promoted to a position in charge of “special diets” for patients. By the 1930s, patients at Ellis Island were for the most part merchant seamen–many of them diagnosed with communicable disease that made it undesirable for them to be treated at a mainland hospital. Sharing a room with one of the guards, Moskelony stayed on the island for three years, becoming accustomed to the demanding schedule and to the isolation of Ellis Island. A musician, Moskelony would play his accordion on holidays and for special events, and eventually began taking classes at Juilliard. In addition, he met his wife–Mary–on the Island. As co-workers, they were unable to marry and both stay there, so Moskelony began working for the newly formed Social Security Beauu, and then the Federal Security Agency. In 1954, he returned to Ellis Island–then under the purview of the Federal Security Agency–in order to oversee the disposal of the Island’s furniture and office equipment. He recommended that the furniture in the wards be burned.