Unique Stories of Ellis Island

The goal of this project is to add unique stories of individuals and their immigration experiences to established Ellis Island history. While most narratives around Ellis Island focus on a specific historical period that focuses on late 19th century and early 20th century European immigration, there is a rich history of individuals with various racial and national identities that came through Ellis Island. Some of these individuals were immigrants, others were detained there, and some individuals were deported from Ellis Island. And, interestingly enough, some passed through Ellis Island twice.

Ferdinand C. Smith

Historic Period: 1924-1954

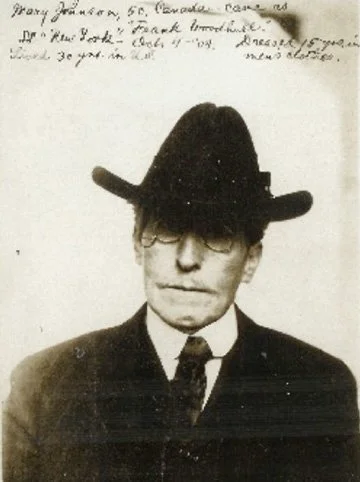

Frank Woodhull

Historic Period: 1892-1924

H.T. Tsiang

Historic Period: 1924-1954

Mohamed Juda

Historic Period: 1892-1924

Thomas W. Matthew and N.E.G.R.O.

Historic Period: 1954-present

Yae Kanogawa Aihara

Historic Period: 1924-1954

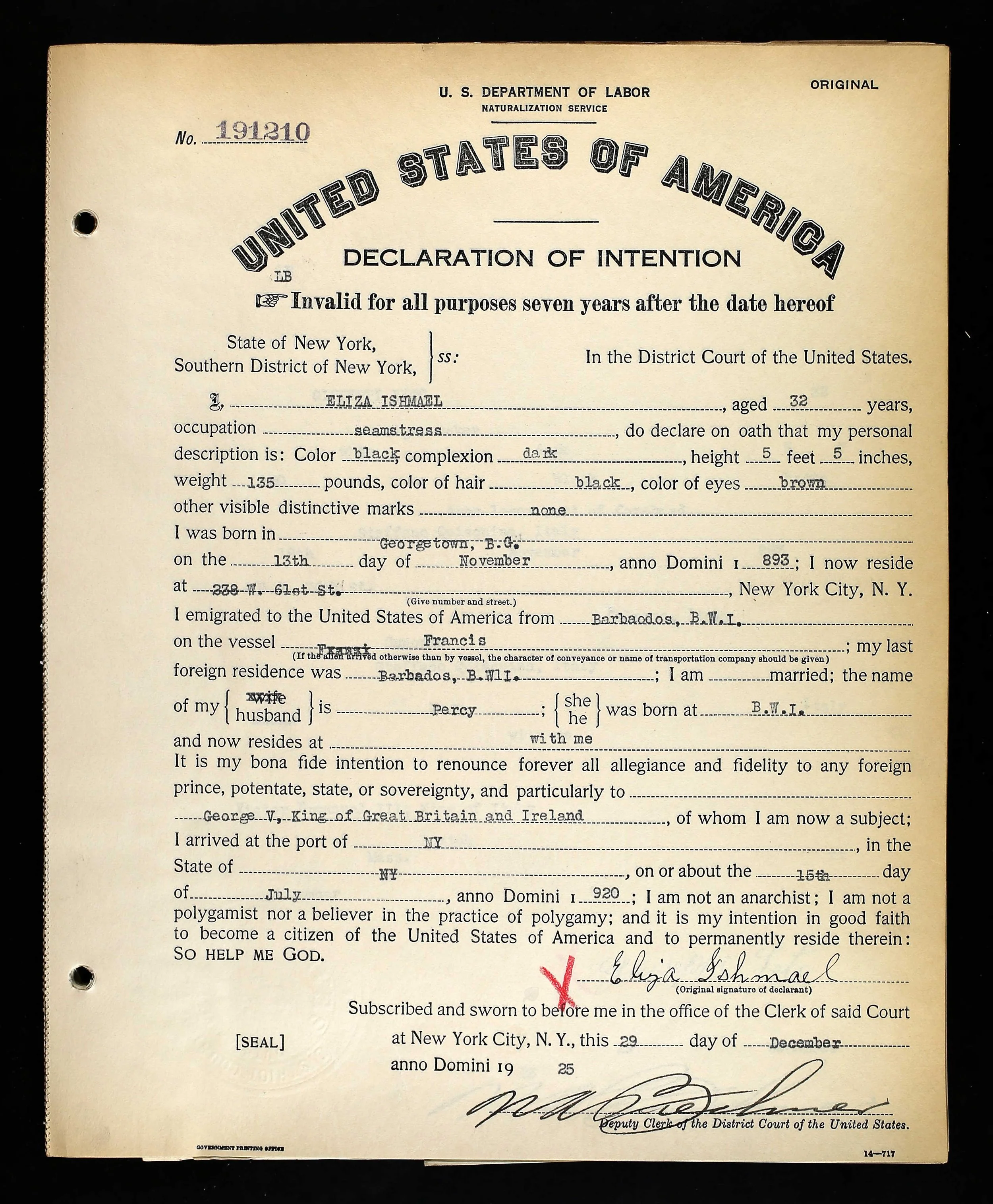

Eliza (Griffith) Ishmael & Percy Ishmael

Historic Period: 1892-1924

Albin Moskelony

Historic Period: 1924-1954

Additional Stories

-

Arthur Bowen (originally Godel) was a college student in Germany during the economic collapse after World War I. As inflation spiraled, he found himself unable to continue his studies and, while playing “21” with an acquaintance at a cafe, decided to stowaway on a ship bound for New York. Bowen and his acquaintance tried hiding in a lifeboat, but were discovered after a couple of days by a sailor who saw their cigarette smoke. Put to work for the remainder of the voyage hauling coal and working in the kitchen, they were transported to Ellis Island. The judge promptly ordered Bowen deported, with no travel to the United States for five years. Bowen replied “Judge, I’ll be back in a week.” After returning to Bremen on the same ship, Bowen again stowed away on the Sierra Nevada, this time hiding in the coal bunker with a number of other people. Again, the stowaways were discovered, and the ship’s captain vowed to imprison Bowen upon their return to Germany. On Ellis Island, he was able to convince guards to put him in a hospital ward, and, after dinner, escaped over the fence on the New Jersey side. Despite the heavy current, he was able to make it to the shore after a few hours. Fifty years later, he was still living in the United States.

-

Falconieri met her husband (Sal) when he was stationed in Naples with the U.S. Navy. He had come to Sicily on leave to see his Aunt, and while he was there met Giuseppa–his cousin. After he returned to duty in Naples, he wrote a letter to his father asking how he would feel if he (Sal) married Josephine. The father gave his permission, and Sal wrote letters back to Josephine declaring his intentions, and visited her in Vittoria nine months later. In 1947, Josephine and Sal arranged to be married in the United States under the Alien Fiancées and Fiancés Act of 1946, which allowed the betrothed of U.S. soldiers to immigrate to the United States outside of the quota system which had been in place since the 1920s. Thousands of women entered the U.S. under this law, including many from China.

The soldier would file a $500 deposit, and was supposed to get married to their betrothed within three months, or the person would have to return to their country. After filing paperwork at the U.S. Consulate in Palermo, Josephine went to Rome and took a Pan American flight to New York La Guardia Airport filled with other “war brides.” When they got to the airport, however, there were problems. Sal and his family were waiting at a different place at the airport, and Josephine–with no one to meet her and no $500 deposit–was taken, with a number of other would-be brides, to Ellis Island.

There, she was shown a bed and offered breakfast, and what may have been a person from a mutual aid society collected money and sent telegrams to the would-be in-laws of the "war brides," who did not, after all, know the women were being held there. Finally, Sal and his family arranged to meet Josephine at Battery Park, and they were reunited there after the deposit was paid and the paperwork completed.

-

In the early 1970s, Phil Buehler and Steven Siegal were high school students interested in film. There was nothing at their school, so they joined a film club on the lower east side of Manhattan. For their project, they decided to row out to Ellis Island, almost completely abandoned since the efforts of Thomas W. Matthew ended in 1971. Strapping a boat to their car, they pulled up to a dilapidated Jersey shore (now Liberty State Park), and rowed out to the island several times in February, 1974. Editing together their footage of the island with photographs and interviews with first generation immigrants, their resulting film, “Ellis Island” (1974), won awards and, in 2024, was the first offering in a New York Times “Op-Docs Encore Series.” Both Buehler and Siegel went on to long careers in photography and filmmaking, including many projects involving ruins. With their Ellis Island project, they were pioneers in the now well-established genre of ruins photography. That said, “ruins” mean very different things, although much of the genre depends upon the mystery and danger of “abandoned” or “forgotten” places. But what was actually “forgotten” here? In the 1970s, immigration was an area of constant debate–just as it is today. The “ruins” were the policies of another era, testament to a shift in both immigration and arguments about immigration from Europe to other parts of the world. And while the Ellis Island in the 1970s may have been overgrown and falling apart, it was very much in the minds of historic preservationists, developers and state- and federal governments, all of which were debating what to do with the structures. There were many ideas, from an entertainment complex to Frank Llyod Wright’s modernist vision of a “City of the Future.” By the 1970s, plans were already underway for the 1980s renovation that would result in the Ellis Island portion of the Statue of Liberty National Monument that we know today.

-

In the years before the closure of Ellis Island In 1954, things were anything but quiet. Yes, Ellis Island was, by that time, no longer an entry point for immigrants. During World War II, it had been transformed into a detention camp for “enemy aliens,” with fences, barbed wire, and a small “exercise yard” where inmates would spend a few minutes each day walking in circles. After the War, these grounds continued to be used by a complex mix of people.

First, there were still “enemy aliens.” Although many had been “repatriated” (deported) or released, there were still almost 200 German detainees on the island by the end of the 1940s. They were joined by suspected Communists–a growing number in the years after World War II. Other people were “detainees,” people who were being kept at Ellis pending the resolution of paperwork problems. Then there were “deportees” who had arrived in the U.S. without proper papers, or who had stowed away, or who had committed crimes in the U.S. and were eligible for deportation even though they immigrated legally.

Multiple nationalities were represented, including a number of Chinese people who had mostly entered the country from Canada. Finally, there were people on the other side of the island (Islands 2 and 3) being treated for physical or psychological ailments. These included merchant marines, but also people who were being detained on Island 1 who had experienced health problems. The number of people detained dwindled by the end of the 1940s, then spiked again with the passage of the Internal Security Act in 1950, a law that strengthened the capacity of the government to deport people it found to be a security threat, including suspected fascists, communists and people supporting totalitarianism. A 1952 article in the New York Times put the number of deportees at almost 1500–these in addition to detainees and enemy aliens (New York Times, 2/14/52).

What was this Ellis Island like? It was, by all accounts, extremely dull. Ellis Island was not designed to be a prison, and, in the 1940s, the Great Hall was converted into a dormitory, while rooms on the mezzanine housed families. Without recreational facilities, people incarcerated at Ellis Island complained over the boredom of their existence. Inevitably, people sought release in games, and gambling–while illegal–was commonplace in the later years of Ellis Island. Anthony Galletta, who served with the Ellis Island Immigration Service from the 1940s until 1954, remembers people gambling with cards, with cockroach races and even with the number of seeds in an orange (National Park Service, 1985). Reportedly, one detainee had built a roulette wheel–although it’s unclear if it was ever put to use (Berger, 1952).

In 1952, this culminated in a bribery case that ultimately resulted in the firing of at least 6 guards and the suspension or disciplining of dozens more. The cases involved guards taking money from detainees to facilitate gambling or to underwrite trips off of the island. As a rule, detainees deposited their money and valuables with the Treasurer’s Office, and they could retrieve that money if they were going off island to buy something. For example, if they were being deported, they could request money to go off island to purchase things for their trip. But for a fee, guards would request money from the Treasury on behalf of detainees so they could join card games or other contests. These were, by all accounts, small amounts of money, and Edward J. Shaugnhessy, then district director of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, underscored the “pettiness” of the corruption (New York Times, 2/15/52).

For further reading:

Berger, Meyer (1952). “6 Guards Out, 26 Accused in Ellis Island Graft Case.” New York Times 2/14/52: 1, 28.

“Ellis Island Graft Charged to 7 More.” New York Times 2/15/52: 42.

National Park Service (1985). Ellis Island Oral History Project, Series AKRF, no. 0041: Interview of Anthony Galletta by Dana Gumb, September 26, 1985, (Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street, 2003).

Pegler-Gordon, Anna (2017). “‘New York Has a Concentration Camp of Its Own’.” Journal of Asian American Studies 20(3): 373-404.

-

Of the 30 million people who immigrated to the United States from Europe between 1850 and 1913, nearly 10 million returned to Europe. Why did they return? We are used to thinking about immigration as a one-way journey, and certainly many people who immigrated to the United States experienced it that way. But for many others, the United States was one stop along multiple migrations. For the most part, the Ellis Island Oral History Project staff interviewed people who were resident in the United States, but there was at least one field trip taken to Northern Ireland, where people who had returned to Ireland were interviewed by Janet Levine.

Ellen Conway (nee Ellen Slane) was 22 years old when she finally decided to leave her small town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. There was “nothing to be made on the land,” she recounted, and her father had died a few years before. Her sisters had already left, one to England, and two others to the United States–she was left on the farm working odd jobs and helping her mother and brother. Finally, she left. “I wanted to be with my sisters [ . . .] I wanted to go away.” As she said of her home village, “There was nothing here for you.”

Boarding the Transylvania in 1929 from Londonderry, she sailed into New York and was processed through Ellis Island, telling officials that she would stay with her sister in Philadelphia. But, as she told the interviewer, “I went to America to make a bit of money [ . . .] I didn’t intend to stay.” It was, after all, the Great Depression, and low-paid, temporary labor was the only available work for a woman with no formal education. Working a variety of domestic jobs in the Philadelphia area, Ellen Conway did make some money, and returned to her small village in Northern Ireland in 1936, shortly before the death of her brother and mother. She remained in her natal home for the remainder of her life, and sat for an interview when she was 91 years old.

It’s worth noting that many families at this tie where stretched across multiple countries by a variety of factors, including the economy, war and colonialism. Like Ellen Conway, they might emigrate elsewhere following on the heels of family members and relatives, but the “better life” they sought might be their natal home–only with more money.

References

Ancestry.com. New York City, Ellis Island Oral Histories, 1892-1976 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Gould John D. 1980. European inter-continental emigration. The road home: Return migration from the USA. Journal of European Economic History 9(1): 41–111.

-

One of the most enduring stories about Ellis Island is that names of immigrants were changed during processing. Here’s an archetypal story from the Ellis Island Oral History Project:

“Yes. Z-A-M-A-R-C-H-O-V-S-K-Y. My father came to this country in 1914 and, of course, he could speak no English at all. When he came to Ellis Island and he was asked what his name was, he did not know what the question was. Standing by another lady who had come with him on the ship, they said to her, "Is this your brother?" And I guess he nodded, and they put on "Brother." Eventually the H was taken off and it was made into Broter. Then when he became a citizen he said he could have changed it back. "But," he said, "it's much easier to spell Broter than Zamarchovsky." And so that was my maiden name.”

(Ellis Island Oral History Project, Series EI, no. 0094: Interview of Esther Horwitz by Paul E. Sigrist, Jr., September 24, 1991, (Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street, 2003), 28 page(s))

We can readily imagine an overworked clerk processing people from dozens of countries, butchering unfamiliar pronunciations, recording the wrong names amidst the chaos. It’s the kind of incompetence we’ve come to stereotypically associate with government bureaucracy.

But historians have long pointed out that officials processing immigrants at Ellis Island weren’t writing down names–they were checking people against the ship’s manifest. That manifest came from the port of departure, not from the port of arrival. Immigration officials might certainly mispronounce that name, but they weren’t writing down someone’s name in any official record. Secondly, people may misunderstand what “processing” meant at Ellis Island in its heyday between 1892 and 1924. Passing through Ellis Island was not registering your identity, nor was it being assigned a “green card.” Applications for citizenship were entirely separate from this process. You were not leaving Ellis Island with an “identity card” of any sort. Even if an official mispronounced a name, it would have no legal weight.

So where do all of these stories of Ellis Island name changes come from? Certainly, popular culture has been one source. In Godfather Part II (1974), a young Vito Corelone arrives at Ellis Island as Vito Andolini from Corelone, but the impatient clerk misunderstands and records his last name as Corelone–changing his name, seemingly forever. While this would never have happened, it would be wrong to dismiss all of the family stories passed down through generations.

First, it’s worth noting that the immigration official at the head of the line in the Great Hall was not the only person of authority a would-be immigrant might meet. There were doctors, guards, translators, mutual aid society employees, volunteers and many others. It is entirely possible that people might be mis-named by one of these, and that this mis-naming might have ramifications.

But the truth is that most of the name changing happened outside of Ellis Island–which is interesting and more complex. In other words, it wasn’t something that happened to someone in a direct way; name changes were in many cases the result of deliberations and negotiations between different people, most importantly the immigrant themselves!

First, names may have been changed before the immigrant even bought the ticket for the voyage to New York. Immigration through Ellis Island tends to be represented as a three-part journey–leaving a homeland, moving through immigration and starting a new life in the United States. But the truth is that these are hardly equal divisions. The first, “leaving a homeland,” may have been a protracted process taking years, and occasioning many, complex negotiations. extending to multiple, interim countries. In the process, names may have shifted and changed multiple times.

“Well, I called him and found out what happened was, when the Heimovi came from the old country he couldn't get a passport in his own name, so he borrowed his cousins' passport, came to the United States, that's what he stayed, instead of being an Obu-Obuina, he stayed a Heimovi”

(Ellis Island Oral History Project, Series El, no. 1163: Interview of Steve G. Basic by Janet Levine, August 17, 2000, (Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street, 2004), 62 page(s))

Second, immigrants may have contemplated changing their name over the course of the voyage, and done so with the intention of a new start in a new country.

“K-A-T-Z-N-E-L-S-O-N. The last part was Nelson. And I already decided before even they asked me my name, I decided that I will change my name because Katznelson was too cumbersome a name. So when they asked me the name I told them Nelson.”

(Ellis Island Oral History Project, Series KECK, no. 0002: Interview of Dr. Samuel Nelson by Edward Applebome, January 16, 1985, (Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street, 2003), 16 page(s))

Finally, names may have changed over the course of life in the United States. First names were often anglicized, but sometimes last names were gradually changed as well–for a variety of reasons. Sometimes, people changed them because they thought they were too difficult for native English speakers:

“I changed my name until after I was working as a medical representative, and nobody could understand, pronounce that name. So I changed my name, legally. It's my, James Legion Melcom. Okay. That's all right now. And my kids have that name.”

(Ellis Island Oral History Project, Series EI, no. 0344: Interview of James Melcon by Janet Levine, July 6, 1993, (Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street, 2003), 38 page(s))

But there were also political reasons as well, as was the case with many people during World War II who changed their names from something they felt sounded too German.

“SCHMIDT: But the T he put on, and we left it that way, because he did not, during the war he changed his name, too, because he was afraid. Here in America.

SIGRIST: During the second world war?”

(Ellis Island Oral History Project, Series EI, no. 0672: Interview of Clara (Klara) Louise Storz Schmidt by Paul E. Sigrist, Jr., September 25, 1995, (Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street, 2004), 69 page(s))

Whatever the reasons and the circumstances, all of these name changes suggest something profound about the times people lived in, the power people felt they had over their own lives, and the aspirations people entertained about life in the United States.

-

Franz Boas was already one of the pre-eminent anthropologists in the United States when he was appointed in 1908 as a researcher to the United States Immigration Commission (called the “Dillingham Commission” after its leader, Senator William Dilllingham). The Commission was formed during a period of strong, anti-immigrant sentiment–after years of record rates of immigration–and its recommendations resulted in the imposition of immigration quotas tied to a percent of existing populations in the United States.

During its four-year period of study, though, the Commission was collecting data, and Boas proposed a far-reaching analysis of immigrant assimilation into the United States. How did immigrants’ physical forms change when they immigrated? How did the physical forms of their children change? Certain physical attributes like the shape of someone’s head (the “Cephalic Index”) was believed to be a durable characteristic of “racial” groups, and that belief contributed to the growth of eugenics, a pseudo-science that held that Europeans were “superior” to other peoples.

After receiving funding from the Commission, Boas appointed a number of investigators to collect physical data in several stages from recent immigrants and their children. Data included various biometrics, as well as family history, and concentrated on a few populations: central Europeans, southern Italians and Jewish peoples, all groups that were the frequent targets of anti-immigration sentiment among xenophobes and racists.

Fanning out through New York, Boas’s team measured people in different parts of New York, and at Ellis Island, where they collected data as immigrants got off the ferries. There are many ethical questions here, since immigrants at Ellis Island were likely to have confused these researchers with the mandatory medical screenings that would have to undergo before being allowed to leave the island. In the end, thousands of immigrants were measured, and, after a year of data collection and analysis, Boas had discovered something that, in the context of the “race science” of the time, was surprising: the bodily forms of immigrant children differed considerably from that of their parents.

Removed from the intense poverty their parents had fled, the children of immigrants were taller, certainly, but the big metric was the size and shape of the head–that “cephalic index.” Since “race science” linked head size and shape to intelligence, this called into question justifications for limiting immigration and imposing quotas on “less intelligent” groups. Boas concluded that “the whole bodily and mental make-up of the immigrants may change.” The report was volume 38 in the Committee’s publications, and Boas published an expanded report in the American Anthropologist in 1912: “Changes in Bodily Form of Descendents of Immigrants.” This led to Boas’s (and U.S. anthropology’s) eventual rejection of eugenics.

For additional reading:

Gravlee, C.C., Bernard, H.R. and Leonard, W.R. (2003), Heredity, Environment, and Cranial Form: A Reanalysis of Boas's Immigrant Data. American Anthropologist, 105: 125-138

Zeidel, Robert F. (2004). Immigrants, Progressives, and Exclusion Politics: The Dillingham Commission, 1900–1927. DeKalb, Ill.: Northern Illinois University Press.

-

Eva Dattner was born during World War II in 1940 Krakow, Poland. Her family was originally from Zywiec but German soldiers invaded six months prior and her mother fled to relatives in Krakow. After Eva’s birth, her mother relocated the family (which included Eva and her older brother, unknown) to Nowy Targ. The war made it difficult for civilians, especially Jews, to access food. Her mother traded gold earrings for potatoes, which led her mother to buy the children gold necklaces later in life, ensuring they always had some gold to trade during times of desperation and need.

Before Eva’s birth, her father joined the Polish army. However, his unit was defeated and he moved to the Russian sector of Poland to work in a bakery. When Germany invaded eastern Poland in 1941, her father was taken to a camp he built bridges for the German invaders. Instead of Yiddish, he spoke German and when he found a merciful soldier, he asked him to help him flee back to his family in Nowy Targ. Her father joined the family in 1942 but the Germans invaded the town shortly thereafter. Her father grabbed the kids and his wife and fled into the woods. Her brother had befriended a family that fed them at night while they hid in the woods during the day. The family’s patriarch obtained false papers and gave her family a Gentile identity.

In the woods, her mother trained her children in their new identity. German soldiers often interrogated children since they were the most likely to slip up. Once both children were well-versed in their new identity, they traveled one town over where they would not be recognized.

From there, they traveled to Krakow to assume their new identity. Family and friends helped them secure work and housing in Lvov, Ukraine where they lived during most of the war as the Slurzewski family. While her brother knew they were Jewish, Eva grew up believing she was Polish during their time Lvov. Her family attended Mass and they practiced Christian traditions like Christmas. When the situation in Krawkow became too dangerous her mother snuck her youngest sister to Lvov, while her father hid his younger brothers in their apartment.

After the Russian army took over Lvov, her family felt safe and they told Eva that she was in fact, Jewish. Eva was confused since she had grown up to have intense Polish pride and practiced Christian traditions. However, she realized that her family did it for her safety. After the war, her parents decided that it was too dangerous to move back to Poland and that it would be better to move to the United States and reunite with her father’s brother. They made their way to the American zone where they could apply for visas.

-

Elizabeth Carter was 5 or 6 years old when she began accompanying her mother to Ellis Island to hire a live-in servant for the Montclair, New Jersey family. In her interview with the National Park Service in the 1990s, she recounts going to a “waiting room” while her mother talked to a uniformed person about a suitable woman who spoke some English. The official gestured to a person, and her mother talked to them about their qualifications. If those qualifications–which included being able to work in a house with children–were satisfied, they would take the person back to Montclair with them.

The servant would cook–Elizabeth’s mother didn't cook–and do some cleaning. They agreed to stay with the family for a year, and, largely, Elizabeth Carter's mother returned to Ellis Island every year to find another live-in servant for her house. Elizabeth remembers being very curious about the different countries people came from, and she still remembers the German one of the servants taught her when she was a child.

She remembered one servant in particular, a woman named Ada Barker, who had come from England with a small child in 1907 and had to leave him with a “children’s home” in Montclair while she was in the employ of the Manly household. Later, Ada Barker married the neighborhood butcher, and left their employ.

It’s a slightly confusing story–for a few reasons. First, Ellis Island employees were not labor brokers. While there had been a “Labor Exchange” at the old immigration station for New York (Castle Garden), there was no similar service at Ellis Island. In fact, would-be immigrants would be deported if they told officials that they were already contracted to work in the United States, since this closely resembled the indentured servitude of the 18th century.

That said, there were still U.S. companies recruiting workers abroad. It is possible that the official Elizabeth's mother talked to was not a federal employee, but a representative of a mutual aid society, helping, in this case, a woman traveling by herself with a child. On the other hand, we have an account from Commissioner William Williams (federal commissioner of immigration from 1903-1905 and 1907-1909), where he implores the reporter to find a young woman whose fiance had back out of marriage a job:

“The girl says she doesn't want to go back, to be laughed at; and I can't let her land. You don't know any lady who wants a servant, do you? She could work! Look at her arms. A nice girl, too. No? Well, I don't know what to do.” (Commissioner William, William Papers, March 1910)

Young women and minors were not supposed to be released from Ellis Island without some kind of assurance they would be “cared for”--a telegram from a relative, a marriage ceremony, etc.

But what about Ada Barker? She was older (33) when she immigrated from England, so it’s unclear what her status might have been. Here the records prove confusing indeed. Elizabeth Carter’s memory was quite accurate–there was an “Ada Barker” who immigrated from Liverpool aboard the “Baltic” in 1907.

Yet she seemed to immigrate twice. There are two ship’s manifests for the Baltic, one in August and the second more than a month later in late September. Both show a woman in the company of two children of the same ages (2 and 3, respectively), one unnamed and the other an Edward Barker. However, the second manifest shows a relative contact for Ada Barker–an Edward Barker in Chicago. Was this the same Ada Barker? Was she turned away the first time, only to return a month later with a husband in Chicago?

-

Samuel Weisstein was born in 1895 in Patsch, Austria, a small village nestled amidst the Austrian Alps. While Viennese Jews enjoyed a degree of freedom under the Habsburg regime's modernization policies, life for Jews in rural Austria remained isolated from these liberal reforms. When Weisstein was nine, his brother moved to New York’s Lower East Side, finding a vibrant Jewish community where he could practice his religion and culture, and most importantly, opportunities far exceeding those available in Patsch.

In 1912, Weisstein journeyed to the United States aboard the S.S. Rotterdam and disembarked at Ellis Island on December 4th. Within a few hours, he was reunited with his brother Morris in the bustling Lower East Side. A few years later, another brother, Abraham, joined the brothers, solidifying their family unit in this burgeoning Jewish enclave. They lived in a cramped tenement across the street from Mount Sinai Hospital, a beacon of medical care specifically for Jews who had previously been denied treatment in public hospitals.

Weisstein worked as a grocer and shared his apartment with his brother Morris, and Morris’ wife and daughter. With the onset of World War I, he registered for military service and declared his intention to become a naturalized citizen. U.S. citizenship gave Samuel options. Life in the tenements was far from idyllic. His tenement probably lacked running water, fresh air, and heat. During the winter of 1918, landlords rationed coal in tenements, which proved deadly for many who succumbed to pneumonia and frostbite. Tenant unions and progressive reforms offered some solace, but real change often required organized action and strikes.

After the war, Weisstein became an American citizen and traveled back to Europe on the S.S. Rotterdam. In Europe he found civil unrest and rising anti-Semitism. Weisstein, who had himself fled for a better life, now found himself a grocer at a crossroads. The question gnawed at him: how could he contribute not just to his own success, but to the well-being of his community internationally? On February 11, 1928, U.S. immigration inspectors detained [a ship’s] Jewish passenger [in Miami]....Documents identified him as thirty-two-year-old Sam Weisstein…[but] after close interrogation, the man confessed that he was…Chaim Josef Listopad, a Jewish carpenter born…in Poland. He had bought the papers in Havana just two weeks earlier, paying fifty dollars to a Jewish stranger wearing a white tropical suit and straw hat.

Samuel Weisstein had decided to use his American citizenship to smuggle Jewish refugees. When U.S immigration inspectors detained Listopad, they had already flagged Samuel’s records. Different men had attempted to use his documents to enter the United States in August and November of 1927. By October 25th, 1928, the real Weisstein was arrested in San Antonio for smuggling Jewish immigrants from Warsaw through the U.S.-Mexico Border.

Ellis Island was not the sole immigration processing center during his time. Immigrants used multiple entry points for different reasons. In Weisstein’s case, Florida and the U.S.-Mexico Border became sites where restrictive immigration policies could be contested. When American policies elevated the restrictive quota system in 1921, it forced immigrants to look for alternatives to Ellis Island. Weisstein saw this change and used it for profit.

The records dried up for Weisstein until 1936, when he married a Russian Jewish woman in New York and then moved to Albany before ultimately settling in Los Angeles. He lived in a multiracial L.A. neighborhood, working as a grocer for most of the 1950s. In 1962, voter registration records show him and his family in Beverly Hills. While his intentions for moving to Beverly Hills are unknown, his movement was during a documented history of blockbusting and white flight. His street was renamed a few years later to Martin Luther King Blvd. and his former address is now lined with low-income housing developments.

Secondary Source:

Garland, L. (2008). Not-quite-closed Gates: Jewish Alien Smuggling in the Post-Quota Years. American Jewish History, 94(3), 197–224. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23887700