Stories of Ellis Island

Yae Kanogawa Aihara

From Immigration to Deportation: 1924-1954

After World War I, rising nativism and xenophobia led to calls to curtail immigration–particularly non-Western and non-Northern European immigration. Quotas were set based on the 1890 census in order to minimize immigration from non-Northern European peoples. People in the Western hemisphere were not part of this quota and continued to immigrate into the United States.

At the same time, the National Origins Act of 1924 limited the number of immigrants and the procedures for immigration to the U.S. had also changed. Instead of judging the fitness of would-be immigrants upon their embarkation, people were increasingly required to apply for visas through the U.S. consulate in their country of origin. No longer a place to process immigration, Ellis Island became a place for internment pending deportation. This was a drastic change. Ellis Island was primarily a site to enter the United States as an immigrant. Now, Ellis Island represented a site where you were told you were not welcome and would be sent back where you came from.

The intent of Ellis Island continued to dramatically change. During World War II and its aftermath, Ellis Island housed a number of people deemed undesirable by the U.S. government, including U.S. residents suspected as being Nazis and, after the war, people accused of being communists.

The Story of Yae Kanogawa

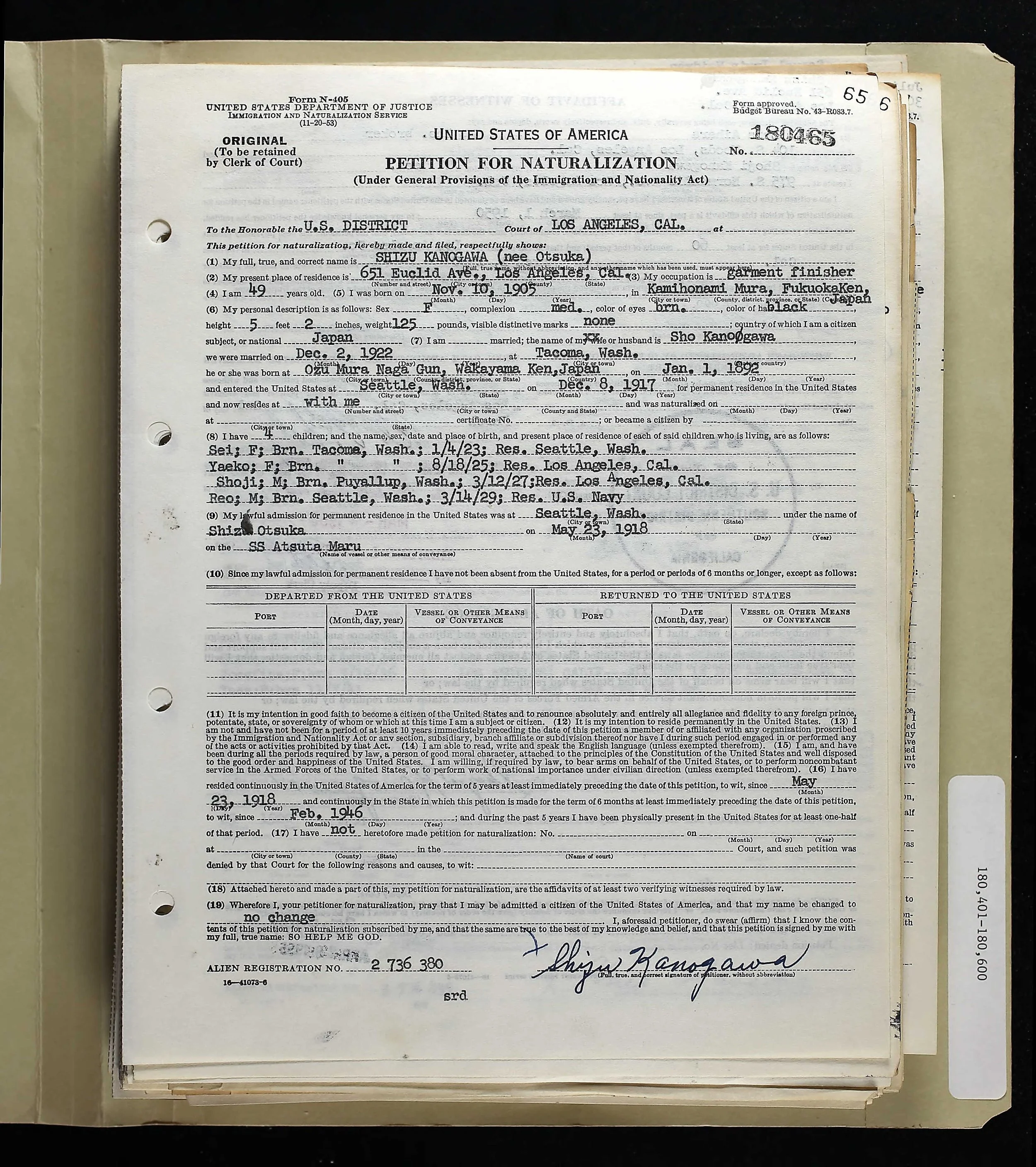

Yae Kanogawa was born to Japanese immigrant parents in Tacoma, Washington, in 1925. As a young girl, her family moved to a racially mixed, immigrant neighborhood in Seattle. She excelled at math and got to skip a grade at school. She also took Japanese language lessons after school every day.

While she had friends who were Chinese, Jewish, and Black, she primarily socialized with Niseis (second-generation Japanese Americans). In high school, she faced racial discrimination:

You couldn't hold office, it was understood. We couldn't go to the prom because it was held in a country club. And even if you were white and Catholic, you couldn't attend the prom. You had to be white and Anglo-Saxon. That's how discriminatory it was. And it was a fact of life in those days.

Despite these restrictive policies, she made the most of her life with her Nisei friends, trying to live an ordinary American teenage life. While at her family’s Buddhist Sunday school, she heard about the Pearl Harbor attacks. That night, the FBI took her father away. Sho Kanogawa, her father, was involved in the Wakayama Kenjinkai (welfare association for Japanese immigrants from the Wakayama Prefecture), the Japanese Chamber of Commerce, and served as an advisor for the Seattle dojo. After spending the night in a Seattle jail, he was moved to Missoula, Missouri.

In February 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. Shizu, Yae’s mother, had two weeks to prepare for relocation, liquidating everything at the grocery store. The family was taken to Puyallup Assembly Center along with 7,000 other Japanese and Japanese Americans from Western Washington and Alaska. Two teachers and the vice principal (a Jewish man) came to Puyallup and held a small graduation ceremony for her and 25 other high school seniors, presenting them with their diplomas. After three months at Puyallup, the federal government moved them to the Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho. In 1943, Sho Kanogawa decided that the family should repatriate to Japan. Yae, her mother, and her brothers packed their belongings and left to Ellis Island.

The Kanogawa family traveled four days by train to meet their father at Ellis Island. They were one of many from Minidoka that had elected to repatriate to Japan. At Ellis Island, guards separated the men and women and she was not able to see her brothers and her father until after dinner. She remembered hugging her father in the dining room for the first time since Pearl Harbor. After dinner, she and her mother slept in a big room lined with cots. The next day, all the other families boarded a ship to Japan. Japan had made a deal with the United States to exchange prisoners of war. The United States incaracertated Japanese soldiers at Ellis Island but it needed more Japanese prisoners of war to bring American soldiers home. They categorize Japanese men, like Sho, as enemy aliens (or prisoners of war) and used them to meet their quota. Once they had enough people on the ship to Japan, they closed the doors. Yae’s family and another family from Portland where left behind at Ellis Island.

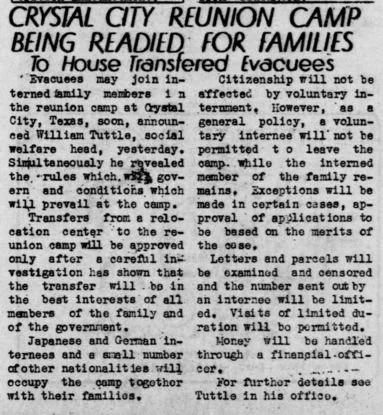

Instead of returning to Minidoka, the Kanogawa family was moved to Crystal City, an internment camp in Texas that was originally designated for Japanese enemy aliens who wanted to live with their families. She remembered traveling from Ellis Island to Texas by train in August 1943: “we actually went through Grand Central Station to, to get on the train to go to Texas. They paraded us all through that whole big station with the MP guards with the rifles.” By the time her family arrived to the camp, it had become a site that incarcerated Issei Japanese men and their families, German and Italian prisoners of war, and Japanese immigrants from Latin America. During the war, the United States kidnapped over 2,000 Latin Japanese, most of whom lived in Peru, and incarcerated them in Crystal City. Though these folks posed no threat to the Allies, the American government used the Latin Japanese abductees as bargaining chips to bring captured U.S. military personnel back to American soil. Yae did not recall socializing with the Latin Japanese abductees who spoke Spanish and had distinct cultures from her own.

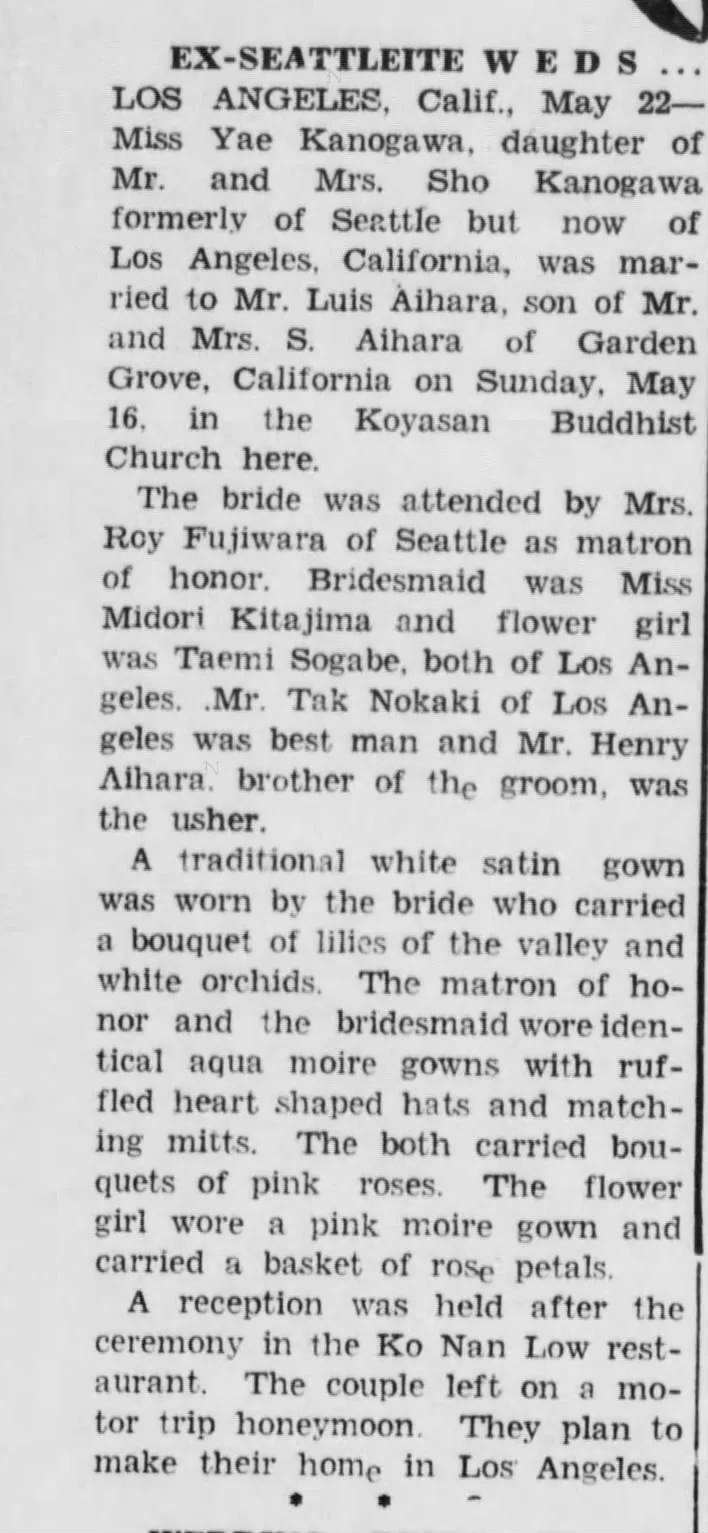

At Crystal City, she attended Japanese school. She was relieved to have her father back with them even if they were still incarcerated. After the war, she and her family moved to Los Angeles where she met Luis Aihara. In 1948, she married Aihara in a Buddhist ceremony. Yae became an active member of the Japanese American community in Southern California, serving as a docent in the Japanese American National Center, participating in the Montebello Women’s Club, and becoming a three-time skydiver. She had a long and fruitful life with her four children and grandchildren.

Secondary Sources

Yae Kanogawa Aihara

Densho Digital Archive - Yae Aihara Interview. (2008). Densho Digital Archive; Densho. https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-221-transcript-2af698b01c.htm

Garcia, H. (2018). The Lesser Known Japanese Internment: Narratives of World War II in the Pacific. Texas A&M University -Corpus Christi; The Mary and Jeff Bell Library. https://www.tamucc.edu/library/exhibits/s/hist4350/page/the-lesser-known-japanese-internment#_ftnref5

Keiro Superstar: Yae Aihara. (2021, November 21). Keiro. https://www.keiro.org/features/keiro-superstar-yae-aihara

2008 - Yae Aihara Interview, Densho Digital Archive; Densho.

https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-221-transcript-2af698b01c.html

The Lesser Known Japanese Internment: Narratives of World War II in the Pacific