Stories of Ellis Island

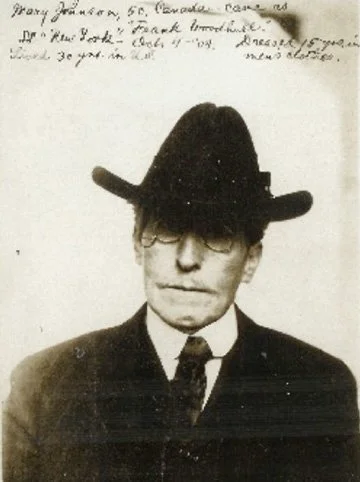

Frank Woodhull

Federal Regulation of Immigration Era: 1892-1924

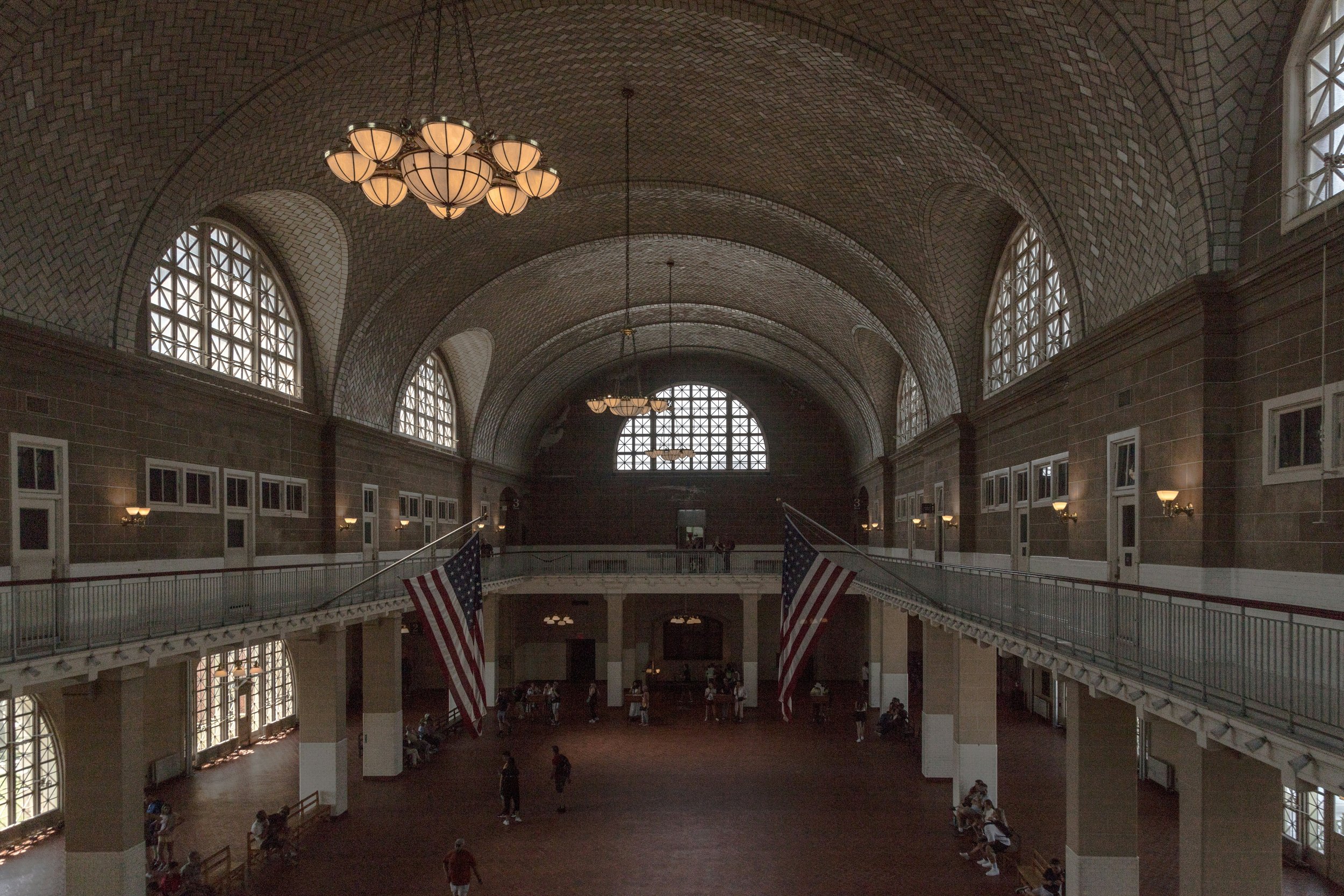

After colonization, Ellis Island passed through several hands, including New York state and finally the federal government, which used it for several fortifications.

Beginning in 1875, the federal government began to take a more active role in the regulation of immigration and began passing laws to exclude people deemed undesirable. In 1882, for example, the first of several “Chinese exclusion acts” was passed during a period of intensive, anti-Asian xenophobia. All of these laws meant a more centralized and bureaucratized approach to U.S. immigration, and construction began at Ellis Island. Opening in 1892, construction continued until 1897, when a fire consumed most of the new construction. After an architectural contest, new plans were drawn up, and new facilities were opened in 1900, with additional construction and island expansion extending over the next decades. This was the most active period for Ellis Island, and from 1892 until the passage of restrictive quotas in 1924, 12 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island.

What was immigration like for them? It was not, as it is today, a lengthy process involving multiple filings, interviews and lawyers. For most of the people arriving at Ellis Island, the process took a few hours and required nothing more than matching one’s name against a ship’s manifest, undergoing a cursory medical examination, and answering a few questions. Passports and visas were not widely used until World War I.

This was the case for approximately 80 percent of people entering through Ellis Island. But other people found their experience there more problematic. Among them, people who were excluded from immigration and people who were found by officials to be undesirable and then deported. These included people lawmakers had excluded as a class as well as people assigned the ambiguous category “LPC”: likely to become a public charge. People singled out for medical problems could also be deported, although many were treated on Ellis Island itself in hospital facilities that still exist on the other side of Ellis Island from the main hall.

The Story of Frank Woodhull

In 1908, Frank Woodhull boarded the ship “New York” out of Southampton, England in steerage. When he arrived in New York, he was ferried out to Ellis Island with other steerage passengers, and joined a snaking line that went past different groups of uniformed men. Some of these were doctors, who gave the passengers a “six-second specialist” examination, looking for signs of communicable disease or mental illness. Something about Woodhull suggested tuberculosis, so he was pulled to the side and taken for an examination.

Before disrobing for the doctor, though, he admitted that he had been born “Mary Johnson,” and had been living for the past fifteen years as a male bookseller in Canada. The case was taken before the Board of Special Inquiry, and they determined, as the New York Times recounts, that Frank Woodhull “was a desirable immigrant and should be allowed to win her livelihood as she saw fit” (New York Times 1908: 6).

Following his release, Woodhull presumably continued on to the destination he had given inspectors: New Orleans. After that, we lose sight of Woodhull. Were it not for a few sensationalist stories in New York newspapers, we would know nothing of this incident; there were many people like Woodhull immigrating into the United States during this period–people who did not fit neatly into the categories utilized by Ellis Island to categorize immigrants. But they, like Woodhull, probably most desired their privacy and the freedom to live their lives.